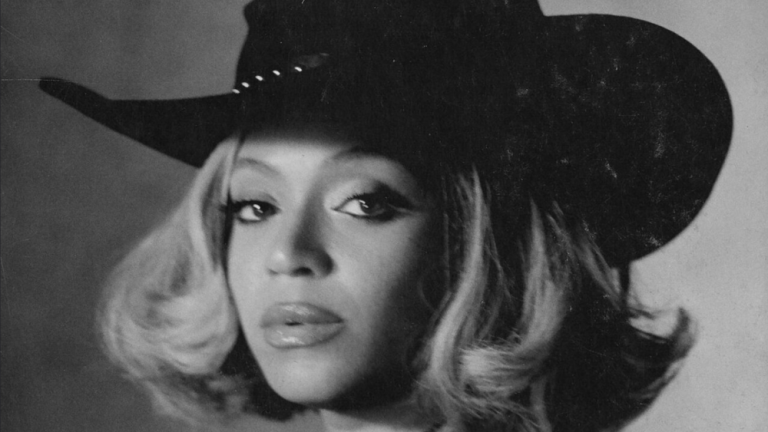

I met Sarah at a strange point in my life. Nico and I were living in Houston, trying to make enough money to support the start of the Olympic dream in earnest and file hundreds of pages of green card paperwork. I started working at a gym, and met Sarah, who was coaching there. She seemed to me like a jacked goddess, totally in command and impossibly experienced at what she did. Since then I’ve followed Sarah from afar, celebrating her when she shares a win and vaguely wondering whether she’s doing okay when she doesn’t post in that strange cadence of being long distance, loose friends over social media. I’ve always been so inspired by her and slightly in awe, so I’m really excited to introduce her to all of you.

Sarah is from Omaha, Nebraska, and grew up in ballet and gymnastics. I asked Sarah what her relationship was like to sports and fitness growing up, and she laughed while twisting her blonde hair around her finger. She said she didn’t consider the hours she spent at the barre as “fitness.” Why is it that we don’t consider athletic pursuits that are traditionally dominated by women as athletic? We have tired discussions about whether or not cheerleading is a sport, while those athletes are nursing broken ribs and icing sprained ankles after hours in the gym. Sarah never thought she would pursue a life in fitness. She was a theater kid and a dancer: sports were for jocks.

But even back then, Sarah was curious. A self-identified autodidact, Sarah sometimes struggles with learning from others, but when the manual is in her hands, she is insatiable. She loves taking on new challenges, and seeing how quickly she can master difficult variations. Many, many years later, Sarah wandered into a Crossfit gym while on vacation from her fast paced gig in management consulting. The strength and body awareness she had gained from gymnastics and dancing, combined with her itch of trying new things met in a perfect storm: she wanted to go all in. Fitness can be both a beautiful and dangerous place to have a personality like Sarah’s. Being talented, disciplined, curious and stubborn can lead down paths that are hard to walk back from. Sarah started to see changes in her body from training, but she knew there was a whole other world out there. Her curiosity was sparked by seeing the insanely lean and cut women who flashed on and off her screen as she scrolled: could she do that? Could she push her body towards a radically different shape and size? She wanted to know if it was possible, and if it was, how to do it. She wanted to explore the edges, the limits of how her body could both look and perform.

A lot of people tuned in for the results.

Sarah is by far the most followed person that I know in person. She has almost 40 thousand followers on Instagram and over 380 thousand on TikTok. Sarah is a gentle, private person, shy in social situations and hesitant to approach people she doesn’t know. Yet she has lived this phase of her life in front of thousands of strangers. When I asked Sarah to do this interview with me, this was a big part of what I wanted to talk about. I’ve found social media to be a really hard space to navigate as an athlete and a human, and I only have a fraction of the number of eyes on me that Sarah does. Turns out, it’s not that nice. Putting a consistently excellent version of your body online all the time is exhausting.

Everyone says they want to see “real people” on social media, or the “struggles behind the scenes.” We both laughed without humor, Sarah rolling her eyes. The numbers don’t lie: people want to see TikTok Sarah: a tanned, toned, lean machine. And since the algorithm demands constant, consistent content, the creation of said content is a constant battle: Sarah feels bloated, but she had planned to shoot today. Should she eat a smaller lunch? Should she push the shoot to the next day? Is there content from when she looked leaner that she can repurpose? Maintaining a facade of fitness is demanding when our bodies naturally ebb and flow.

And after all that? Here come the internet trolls: “That doesn’t work, she doesn’t know what she’s talking about, she’s fake…” etc. etc. There is a double standard in the industry between men and women creating content that gives advice. (Aka most all content from fitness influencers.) Female creators have to work twice as hard to get people to take them seriously, and trust the advice they have worked so hard to learn to give. Sarah has become exhausted by the process of creating content that is exciting, stimulating, educational and sexy, only to have thousands of strangers on the internet tell her how, or how not, to do her job.

Even if she wanted to do this forever, she can’t. Another thing the algorithm doesn’t want to see? Aging bodies. Careers online in fitness are only good for as long as your youth holds, then we’re swiping to the next young thing. Sarah says she’s curious about what comes next in the body positivity movement. She pointed out that body positivity is mostly targeted at women in bigger bodies: not women in stronger, or, god forbid, older bodies. Women with muscle aren’t beautiful or feminine: at best we’re manly, at worst people question whether we deserve to be women at all, or debate whether we can tolerate more pain or violence.

So Sarah has been slowly extracting herself from the world of Dexa scans and weigh ins, carb cuts and shiny content. She’s discovered that a lot of that world doesn’t feel as good as it looks. She’s still training, and connecting to her body, but in a way that feels gentler and kinder. She’s rediscovered dance, is dabbling in calisthenics, and staying curious about new challenges: she’s ready for a different adventure.

A lot of that new adventure is about ideas and words. I’m so inspired by Sarah’s ability to think critically about the fitness and social media machine, and how we as athletes value our bodies, work and our contributions to society. So wherever Sarah is going I know she’ll go there with determination, thoughtfulness and curiosity, and I can’t wait to watch it from afar. Or maybe I won’t, but I’ll worry a little less when she doesn’t post from now on. I’ll know that she’s teaching herself a new handstand, or reading Aristotle, or something magical in between.

For big thoughts, Sarah recommends…

The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf and Perfect Me by Heather Widdows for critiques/analyses of beauty standards. She says, “neither book is perfect but both are thought-provoking and interesting.”

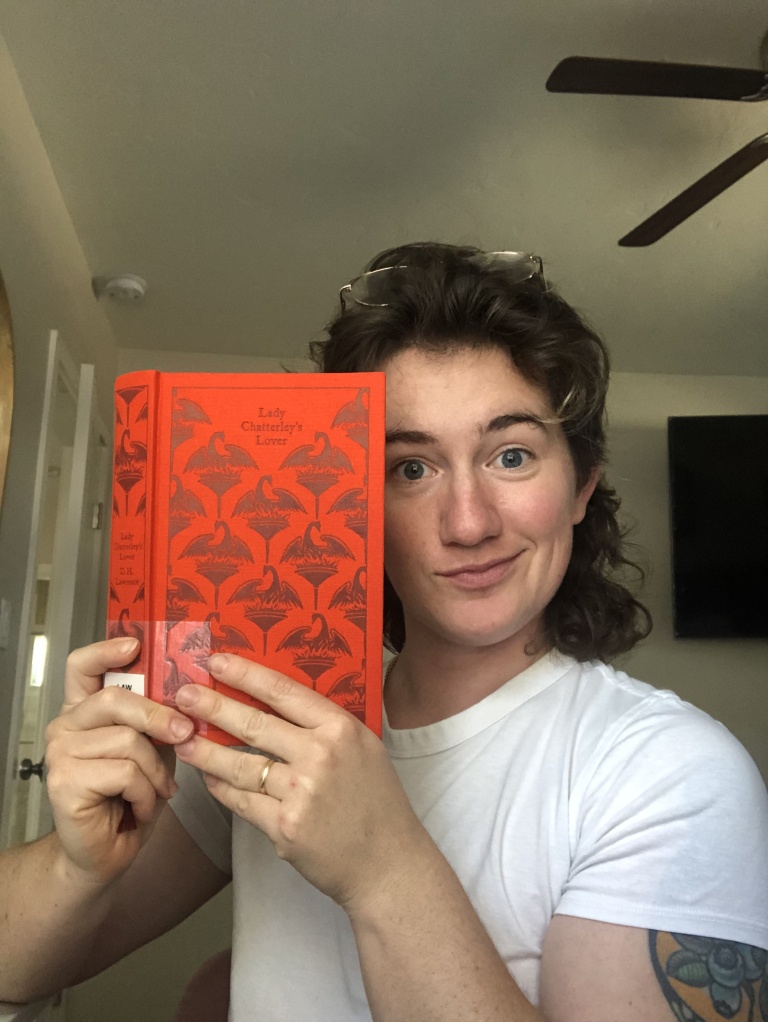

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde for a study of vanity.

The Human Condition by Hannah Arendt, not for fitness people specifically but just an interesting study on the meaning and value of work.

***

You can follow Sarah on Instagram @sarahherse, and check out her incredible fitness app here.

Written by Skyler Espinoza

Photo Credit to Focused Fitness Media